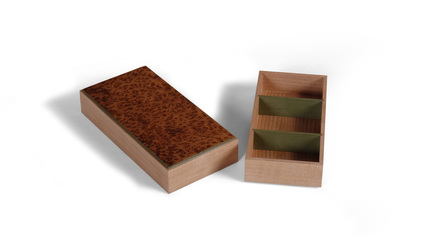

This one feels like a big deal. It's box 50, after all, but I also think it's important because it's a refinement of a box that I've been making for several years: my old friend, the two compartment box (right). It has smaller overall dimensions (1 1/2 in. by 3 in. by 6 in. versus 2 in. by 5 in. by 8 in.), has one compartment instead of two, uses a more stylish pull, and has thinner sides and top. These differences make the box simpler and more delicate, but what makes it more elegant is the inward sloping sides and milk painted edges on the top. These are subtle things, certainly, but they make a big difference. However, I'm kicking myself a bit because had I used a slightly different pull, a slimmed down version of the one I used on box 46, this would be a perfect little box. I guess I'll have to make it again in the near future, just not before I finish the 52 box project. That's quickly coming to a close. And I already have the last two boxes designed (in fact, box 51 is just about done). The inspiration for this box came from the second box I ever made (many, many years ago). We still have that box. It sits on my wife's dresser. It's at least 1 in. taller, and is closer to square in width and length. It also has sloping sides, but I made them by starting out with thick sides and planing the slope into them after assembly. This box has 3/16 in. thick sides. There are compound miters at the corner that result in the inward slope. As I did for boxes 13, 14, and 15, I used a "wedge" to cut the compound miters, the rabbets, and the top and bottom edges. I like the technique because the wedge guarantees that all of the angles will be correct. As a result of the more refined construction, this box is more elegant than the original. I'd like to say that a lot of careful thought went into the design of this box, but that wouldn't be true. I looked at the older box, asked how I would make it now, and the answer came to me quickly. Make is shorter, make it a rectangle, and use compound miters at the corner. I also used the bottom to create a shadow line at the bottom. And the pull is similar to others that I've used. What I did, in other words, was take design details that I've been using this past year and put them together in a new way. In a way, there's nothing new hear, but in truth its a very new box. And it's one of favorites. I love its delicacy, elegance, and the beautiful fabric inside. I don't think I have anything else to say about this one, but you're more than welcome to ask questions if you have them. Here are a few random thoughts.

5 Comments

Here's the second of two boxes that I made using the same dimensions for the box body, and the same species of wood (actually, both boxes were made from the same board). The first box was posted last week. I wanted to see how different, how unique, I could make two boxes that had these similarities, that were the same box at their core. There was an easy way to make them different. I could have given one of them eight legs and a head, making it a spider box. Or some other whimsical nonsense. I wanted more of a challenge, so I limited myself to variations in the lid, pull, and base. What's funny is that although I did make two boxes with unique souls, I also ended up with two boxes that are clearly from the hand of the same maker. I suppose that's really not surprising, but when I first put them next two one another I was struck by it. Actually, it makes me happy. I think it shows an admirable level of design maturity (I'm sure I'm flattering myself in thinking this). I took a narrow set of design parameters and created two distinct boxes that are clearly expressions of my aesthetic. I didn't have to resort to outlandish and absurd differences to get the job done. A few subtle changes is all it took. I believe this means that I've grown as a designer, developed a better understanding of how to apply my aesthetic. This also means, I believe, that my aesthetic is flexible, and this makes me happy, too (a point further illustrated by box 45). Well, that's enough philosophic ruminating. Let's get to the box at hand. I think that as I talk about what I was thinking as I designed this box I won't be able to avoid talking about the first box, but that should be instructive. I'll start with the pulls. On this box the pull is cocobolo banding that wraps around all four sides of the box. I made it just as I did the pull/lid keeper on box 36. It's less than 1/16 in. proud of the sides, but this is more than enough for your fingers to get hold of and pull the lid off. This is a very different style of pull than the one I used on the first box. But, notice that this pull is cocobolo, and that I wrapped the pull for the first box in brown thread. Brown is a nice complimentary color for the cherry box and green milk paint. It makes a great third color to introduce. Using it in the pull means that there will be less of it than both the warm, earthy reddish brown of the cherry and the lovely green milk paint. I'll admit that I chose cocobolo without thinking of the connection to the brown thread, but I certainly chose it for the same reasons that I went with brown thread. It's a strong wood that works well as a tertiary color. (As a primary or secondary wood, cocobolo becomes is overbearing, I think.) At any rate, the pull turned out to be something that both distinguished the second box from the first, but also connected the two. On to the base. I've used this style before (boxes 41, 42, and 44), and I'm starting to really like it. It's plywood with a shopsawn veneer on the bottom face and fabric on the top face. The edges are painted with the same custom green milk paint as the edges of the top. The bottom's edge is thicker than what you see of the top's edge, so the bottom has more weight and can anchor the box. I made this bottom a bit different that I did when I used it previously. The plywood portion of the bottom fits into a rabbet in the box. This means that there is a fairly deep rabbet around the top edge of the bottom, which results in a dark, distinct shadow line. The box seems to float above the bottom. I like it. As for the top, I made it by gluing a panel into a rabbet and then cutting the box body in two. It's quite similar to, but still quite different from the top I used for the first box (a panel that fits into a rabbet). The liner does not keep the lid in place, the pull does. As I did with the first box, I painted the edge of the panel to create separation between the box sides and the lid panel, and I did it for the same reason. It allows the panel to pop as if it were a second species, or a highly figured piece of cherry even though it's cut from the exact same board as the sides. The green creates a visual boarder around the panel. Random thoughts time let it be.

This is the first of two boxes that I made using the same dimensions for the box itself (that is, not including feet, lids, pulls, etc.). I even made both boxes from the same piece of cherry. Why? I wanted to see how different I could make them. Next week I'll post the second box. Both boxes were designed to hold tea packets. I started from the known dimensions of a tea packet (and it's a common size) and worked out from there. There are three slots for tea. These are created by a liner that is dry fit in the box. After adding up all of the involved dimensions (side thickness, liner thickness, top/bottom thickness, width and height of a tea packet, etc.), I knew the width, length, and height of the box. From there is was a matter of figuring out how to give each box its own unique soul. The first two decisions I made about this box is that it would sit atop some type of foot structure and that I would not cut the sides apart to make a lid (as I did on box 30, for example). I tackled the lid first. I went with an old friend: The lid that sits down in a rabbet cut into the inside face of the sides. A lid this big would need a substantial pull. Last week, I used some cool thread wrap pulls on a large tea cabinet. I decided to adapt that pull style to this box. This pull is much larger (the horizontal bar is 4 1/2 in. long), which gave me enough meat to work with that I could bevel the ends of the pull and the ends of the feet. The bar and feet are made from basswood, and the thread is a brown embroidery thread (thicker is better for this purpose). I applied shellac to the basswood before wrapping the thread. I think the pull turned out quite well and it's a style of pull that I'll continue to explore and develop. For the sake of stability, I made the lid from plywood, gluing shopsawn veneers to the top and bottom faces. The veneers were cut from the same board as the sides. The plywood top also allowed me to glue the pull to the lid without any concern that wood movement might eventually pop the pull off. The edges of the lid are painted with a custom green milk paint. I don't know if I've ever explained why I occasionally paint the edge of lid. Here it creates separation between the lid and the sides. Without this bit of color, the lid and sides would simply melt into one another, because they're made from the same piece of wood. The color and grain match is perfect, and without the green you'd just have a big, indistinct blah. This little strip of color creates a border between the two, which allows the beautiful warmth of the cherry's color and its calm, but elegant grain really pop. The box is subtle and unassuming but still possesses a striking beauty. This approach appeals to me far more than slapping a wildly figured or super-contrasty wood on the box as a lid. (As I see it the dependence of figured and contrasting wood is lazy design.) After I figured out the lid and pull, it was easy to work out what the box would be sitting on. The feet are just a modified version of the pull. There are two long horizontal pieces and the feet are much longer, too. This design creates a balance between what's above and below the box. The bottom is plywood, which is important because the best (and most stable) way to attach the feet is to glue them on. However, if they had been glued to a solid wood bottom, the bottom's movement definitely would have either pulled the feet apart or caused the bottom to split. So, plywood it is. There's a shopsawn veneer on the bottom face of the plywood. And like the feet themselves, the veneer is cut from the same piece of cherry as the box and lid. By the way, the top surface of the bottom is covered in a very nice fabric. Sure, you'll never see it because of tea packets. But it's there for the occasional glimpse, to show that every detail has been carefully considered. Well, I think that's enough. Here are the random thoughts, which I enjoy writing even if no one enjoys reading them.

This is box 37, which I made at the same time I was making box 36. The have the same dimensions and were made with the same construction techniques, but they clearly are not the same box. I like each of them individually, but I think they're better off as a pair. The underlying familial connection makes their individual beauty shine even brighter. When I first got the notion of making 52 boxes in 52 weeks, I envisioned making individual boxes, but I've grown fond of building a pair of boxes around a few basic design ideas (proportions, use of color, etc.), taking each box in a different direction while letting their bones tie them together quietly. I wonder how many boxes I could do this with. I think three would work nicely. More than that and perhaps the magic is gone. So, this box. It's cherry, with kingwood pulls. It's a great pairing. Kingwood is in the same genus (dalbergia) as cocobolo rosewood, and African blackwood, so it's no surprise that it compliments cherry so well. The pulls are mortised into the lid. I cut a matching mortise in the box for each pull. When the lid is on the box, the pulls register in the box's mortises and hold the lid in place. It's simple and clean. I like it. Because this box is so small (1 3/4 in. tall by 2 in. wide by 4 in. long) it was critical that I pick the right piece of cherry for the sides. It needed to be riftsawn with straight, tight grain. The grain on the piece I used is proportioned perfectly for the box's size. I think that matching the grain's proportion to the box's is something that many woodworker's do not think about, which is a shame. Let's say you make this box from curly maple—and I think it would look good in curly maple—the curl would need to be very tight, so that you get a lot of little ripples across the sides. This makes the little box look like it was made from curly maple. Big, rolling curls just wouldn't have the same pop. The box might look splotchy or vaguely figured as a result—and it really look like it was made from curly maple. The same goes for the fabric I chose. Cherry goes well with blue, so I pulled out my blue fabrics. But the visible area of the bottom and lid are quite small. A fabric with a large pattern would look odd, so I went for one that has a small flower (in blue) all over it. It gives the sense that the fabric was made for a box just this size. A big pattern would suggest that I used a fabric meant for something big, like a quilt, and crammed it into this little box. Perhaps I'm odd for thinking about the fabric I use in this way, but I really do believe it's important that all the details of a box be appropriately proportioned to harmonize with the box's proportions (this, I believe, is also true of all furniture—no matter the size). And my attention to this particular detail is only an example of the level of attention one must pay to the details when designing. Everything must be considered. OK, let's get random.

This box came out of nowhere. As I was finishing box 35, I was a bit frustrated because the quality of workmanship is a bit lower than I'd like. There are a few gaps in the bird's beak joints. So, I decided to make a box and make it as perfectly as I could. For some reason the first thing that popped into my head at this point was a very small ebony box. I thought that if I could come up with a good design and execute it perfectly, then ebony would make the box seem like a little jewel. I don't know if I accomplished my goal, but I really like this box. For the most part it's a pretty normal box. It's 2 in. wide and 4 in. long. The sides are 1 3/4 in. tall. The top and bottom have shopsawn ebony veneer on the outside faces, and fabric on the inside faces. There's some shopmade poplar plywood between the ebony and fabric. The top and bottom are glued into rabbets cut into the sides. I glued up the sides, glued in the top and bottom, then cut the lid free. And here's where to box takes an unexpected turn. A common approach to keeping this style of lid on it's box is to use an insert on the inside of the box. I used this technique on boxes 12, 28, 29, and 30. When I was designing this box, I decided not to use an insert. Instead, I though that I might inlay some thin circles into the front and back of the box. The inlay would be glued into the lid, but not the box, so you could pull the top off, but when the top was on, the inlaid circle would lock into the half-circle mortise in the box bottom and keep the lid in place. I considered several other shapes, too. But, honestly, all of that seemed like a colossal pain to make. So, I thought some more about it. Here's what I came up with, and it wasn't hard to do. After cutting the lid free and cleaning up the sawn edges of the lid and box, I routed a small rabbet into the lid and box. I then made some strips of maple that were just wider than the "groove" created when I put the lid on the box. I also left the maple a bit thicker than the groove was deep, so that it was just a few hairs proud of the ebony. My plan was to paint the maple, then glue it into the rabbet in the lid. That's what I did. The green strips are mitered at the corner. The strips automatically fit into the rabbet it the bottom and hold the lid on the box. There's not much else to say about this box, but I do want to explain why I painted the strips that hold the lid on the bottom. I thought about using solid wood, and quickly ran through the species I have on hand, like cherry, walnut, apple, mahogany, madrone, white oak, maple, holly (It's really not very good holly. I should not have bought it.), etc. None of them were the right color. And then there's the issue of grain. Ebony's grain is so difficult to see, that even a wood with very little grain, like madrone or apple, looks odd against it. I also thought about using curly maple, which can look great with ebony, but the strips are so small that I feared the maple would no longer look curly. Also, ebony is so lacking in variation of color, that other woods look odd juxtaposed against it when ebony is the primary wood. So, I decided to go with milk paint. It shouldn't be a surprise that I think it looks great. One last point about the strips. I left them proud of the ebony for a few different reasons. First, I wanted there to be a tactile indication of how the lid comes off. When you put your fingers on the lid, you feel the strips slightly and can grasp them to help pull off the lid. Second, it would be damn near impossible to get them truly flush with the ebony. Normally, you'd glue them in place and then plane them flush, but I couldn't do that because it would remove the paint. Of course, you could remove material from the inside face until the outside was flush, but because a bit of the inside face is exposed and painted, I couldn't do that, either. A third option would be to plane the strips flush to the ebony before I painted them, but then they would no longer be flush after I painted them and you would feel that. So, I intentionally made them proud, and they're proud enough that it's clearly intentional. Good design is always intentional. Alrighty, then, here's some random thoughts.

This box is similar to box 33. They have the same dimensions, the bottoms were constructed in the same way, and both boxes have lids that sit inside a rabbet. But for all that similarity, they really are quite different. I made them both as an exercise to see if I could make two boxes with their own souls even though they had several important similarities. If I'm being honest, I'll admit that it was as I was designing this box that I realized a similar one would work nicely with box 32, so I began designing this box and box 33 in parallel. It was fun to make two boxes at the same time, using the same milling procedures, the same machinery setups, etc. and end up with two distinct boxes. This version of the box sprung from my dissatisfaction with box 6, which is the one box I've made so far during this adventure that I don't even remotely like. Box 6 is a second take on a box I made several years ago (that's it in the photo just over there, on the right). This time I went back to the original woods, cherry and white pine. It's a very good combination. This pine is some seriously old stuff that grew wickedly slow. I have friend who likes old timber frames (OK, it's John Tetreault from Fine Woodworking). He's using a bunch of old frame parts to make a wood shed and art studio on his property. He cut some pine timbers (about 8 in. by 8 in.) short and gave me the offcuts. It has super tight grain and a beautiful, lustrous color. The white pine that you can buy at the lumber yard now is a sad, pale semblance to the good old stuff. To match the tight grain of the white pine top, I used some cherry edge grain that also had very tight grain lines. Although the woods are the same, I changed the dimensions dramatically. The original is 2 in. tall, 5 in. wide and 8 in. long. I wanted this one to be small and more rectangular. It's about 1 1/2 in. tall, 2 in. wide and 6 in. long. The divider is 2 in. from one end. I know I've harped about the importance of proportions, so I'll go easy this week, but good proportions are so terribly important. Get them wrong and the box is simply bad. The original version of the box had cocobolo pulls. I didn't want to repeat that, so I went with painted pulls. I wanted them to be green, and I got lucky that I had some divider material left over from box 31. I just ripped it to width, cut it to length and then painted the ends. Perfect. I like the green with the cherry and pine. Another slight change from the original involves the fabric on the inside. Back then I glued fabric to some thin foam. This time I glued it to the bottom before I installed the bottom in the box. I really like the clean look of the fabric in this box. (I also used a different blue fabric. This one has a softer look.) Please humor me as I let fly with a few random thoughts.

I made this box to fit inside the rectangular and horizontal box in the set of wall-hung display boxes that I posted last week (box 32). The interior dimensions of that display box determined the dimensions of this box. And I knew it was going to be a simple box with a top sitting in a rabbet, and my standard bottom (plywood covered in shopsawn veneer and glued into a rabbet). But that's all I knew. There were important questions left to answer: What to do with the top? And what about the interior? And I had no idea what kind of pull I should use. But before I could answer those questions, I needed to figure out the box body first. I had the perfect piece of wood for it. This past summer when I was working at the Lie-NIelsen open house up in Maine, I began rummaging through the exotic woods for sale at the bench of Travis Knapp, who runs the eBay store RareWoodsUS. I found a 12 in. long blank about 1 3/4 in. square. I didn't know what species it was, but the edge grain was amazing: beautiful, tight, straight grain. And the color was fantastic, too. Travis said it was kingwood. I bought it, went back to my bench, then planed that edge grain clean. I feel in love. I'd been sitting on that piece, waiting for the right box to come along. This was the box. I knew that the wood's color would go great with the brown of the sake set. And the straight lines would compliment the vertical grain Douglas fir of the display boxes. I've never used an exotic wood for the body of a box—I prefer to save it for pulls and other small accents—but I'll have to try it again soon. If I can just find another piece of kingwood with grain like this! Knowing that this box would sit inside one of the display boxes helped me figure out what to do with the top: Paint it green. I used Lexington green milk paint, knowing that a darker green would stand out against the light green I used for the backs of the display boxes. And the dark Lexington green would compliment the rich brown of the kingwood. But the pull is really part of the top, and I had no idea what to do. So, I made and finished the box, painted the lid, and then set the lid in the display box as it hung on a small piece of drywall (temporarily, for photography). Mike was looking with me and suggested drilling a hole through the top and painting the inside edge created. "Paint it white," he said, "because the inside of the sake set pieces is also white." Good idea, I thought. He then said, "Make it a little round scoop instead of a hole." I took that idea and ran with it. The hole is shallow and has a flat bottom. I painted it with snow white milk paint. I then made a pull from ebony. The shape took a while. I fit the "tenon" part to the hole and then started shaping, putting the pull in place and taking a look, then going back to work on the shape. I like the final shape. It's low, so it doesn't overshadow the box, and the curve is very subtle. I shaped it all with a chisel and a rasp. And I really like the graphics of the rectangular green top with a white circle in the middle that's bisected by the thin rectangular ebony pull. For the interior, I put into play a suggestion made to me by another Fine Woodworking colleague, John Tetreault (he's a great designer and furniture maker, too.) We were discussing a group of 40 boxes (not part of this 52 box business) that I am making and he suggested that instead of painting the interior face of the bottoms, I should just glue some fabric to them. I liked the idea and decided to try it out here. I set the box over several different pieces (various colors, patterns, etc.) and settled on a piece that has brown flowers on it. It looks great. And glueing it to the bottom results in a much cleaner look than when I glue it to a thin foam pad. I'm fortunate to work with such great designers. I doubt I executed either Mike's or John's suggestion as they would have, but that's the way it should be. Well, then here are some random thoughts.

I suppose I should address the elephant on the wall first. Some might contest that this week I've not made a box. To this objection I say, "tis but a silly word, box. It means nothing to me." Perhaps that's not sufficient. Here's what I really think on the matter. I set the rules for this challenge and I decide what counts as a box. That too sounds a bit pissy, but so it goes. This is a wall mounted box designed to hold, keep safe, and display a sake set that belonged to my maternal grandparents. I can remember it in their house for as long as I can remember going to their house. My grandfather died first, about three years ago, and then my grandmother died little more than a year later. I went to their house after her funeral and was allowed to take this as a memento. I always liked it. I still do. If you look closely, you can see that a few of the cups were broken through the years and glued back together. I like that. The set meant something to my grandmother—enough that she kept gluing cups together—and so it means all the more to me. Well, that's the story of the sake set, or at least as much as I'd like tell in a public forum. I began thinking of how to display the carafe (I have no idea what the proper word is) and five small cups, and went through a lot of ideas for the overall design before I settled on using a small box for each piece. I was drawn to individual boxes because it would allow me arrange them in a nice geometric pattern (I do love me some geometric patterns) and to present each piece as something significant in itself. It then took several pages in the sketchbook to find the arrangement that I liked best. It's the one you see here. This left me with a bit of a problem: Why the hell do I need that other long box at the bottom? I don't know but it balances the pattern well, so I stuck with it. I originally planned to put a drawer inside it. But the proportions aren't right for a drawer (the box isn't deep enough for one thing). Then, in a moment of opportunistic genius, I realized that I could put a box in there! Two birds, meet one stone. At the risk of spoiling the surprise even more, this smaller box that goes inside the box at the bottom will be box 32. My thought next turned to how to make the boxes and the finer details. I wanted simplicity. The boxes are not what's on display here. A simple mitered box would fade into the background, but provide an elegant frame around each piece. The back of the box, I knew, needed to be painted a light color to provide some luminescence inside the box, and so that the sake set pieces would stand out against the back. Green can go nicely with brown, so I set about mixing up a custom green milk paint. This one is mixed from marigold yellow, Federal blue, and buttercream. The wood species fell into place after that. Douglas fir looks great with green and brown. Vertical grain Douglas fir looks awesome on miter boxes. The grain on the fir I used here is so tight and fine. It's the perfect amount of subtle for the task at hand. If you're curious, the unit of measure for subtlety is snurtles and this fir comes in at exactly eight snurtles. (Also, the fir came from a piece of roughsawn 8/4 vertical grain fir that I bought from a former FWW editor. I actually bought two pieces from him. Always buy good lumber when you come across it. Eventually, you'll find a use for it, even if it's after your wife leaves you because the entire garage is filled to the ceiling with glorious lumber, and the spare bedroom holds all the shorts.) I don't know if there's anything else to say. I suspect I'll have more next week when I reveal the little box that fits inside the bigger box at the bottom of this arrangement. Until then, feast (or starve, depending upon your opinion of my eccentrities) yourselves on a few random thoughts.

This is a simple box. It's just a small piece of veneer, some quiet wood for the sides, and a bit of milk paint as an accent. But it's stunningly beautiful. I think this is because of the balance struck between them. It certainly helps that the proportions are spot on—good bones are always beautiful. (It's less than 2 in. tall, 4 in. wide and 8 in. long.) And the box is an excellent example of using woods (and colors) that compliment rather than contrast with one another. Sometimes, a plan comes together. And like Hannibal, I love it when that happens. Let's start with the burl veneer I used on the top. I have no idea what species of wood it is. I was given three flitches of this veneer by a friend. The color is fantastic. So, too, is the figure. But what really makes this veneer work on this box is that the individual "burls" are small. It's super intense, but it's also well-proportioned for a small box. Big, loose burl wouldn't have looked right. It would have been out of scale to the rest of the box and that would have disrupted the box's harmony. That might sound silly—or even overly precious—but when you design a box or piece of furniture, you must give thought to every detail. I chose riftsawn madrone for the sides. I could have used cherry, but cherry has too much red and pink in it. I could have gone with walnut, but walnut is too dark for this veneer. Madrone is a finely grained wood with a lovely earthy brown sapwood. The grain on the piece I used was straight and tight. It's quiet—the perfect compliment to the muscular burl on top. There can be only one dominant wood in any one piece. The others should serve to bolster it's strength. (By the way, this piece of madrone was small, an offcut from a wall cabinet I made years ago. It's been hanging out in the shop, waiting for the right box to come along. It finally did. It's wonderful how little pieces of wood, long forgotten, pop up from the depths of memory at just the right moment. And this piece did. I remembered everything about it: dimensions, color, and grain. Perhaps I grow too attached to the lumber I own.) The green milk paint was easy to pick. The madrone is close enough in color and the fineness of its grain to apple that I knew that this green (which I used on box 25) would work well as an accent. Deciding to paint just the edges of the top (and bottom) was easy, too. I've done that before and it works well to separate the box sides from the top. Here it emphasizes the shape and figure of the top. Figuring out what to do on the inside of the box was harder. At first, I was going to paint the bottom and the dividers (and have more dividers), but that seemed too busy for such an understated box. I eventually worked my way to a bottom made from plywood and shopsawn veneer (riftsawn madrone), and just two dividers painted green. By the way, in the past I would have joined the dividers to the sides with a bird's mouth joint, but here I went with a simple dado. I gambled that painted dividers would look better with a squared end in a shallow dado. I think the gamble paid off. The joint emphasizes the distinct difference between the sides and dividers. In this case, that's a good thing. Here's something that struck me after I had completed the box. It was easy to design and even easier to build. That sounds tremendously arrogant, I'm sure, but let me explain why I say it. The design part was easy, because I was pulling together several design details that I knew worked: the top that's a bit proud of the sides (and has painted edges), a top that slides over the bottom, tightly figured veneered set against riftsawn lumber, dividers used to create a cool geometric pattern. I've used all of the design details in this box before. I just put them together in a fresh way. This excites me, because it means that maybe, just maybe, I'm getting to the point where my design aesthetic has a well-define grammar and vocabulary that can be relied upon to produce beautiful work. The danger is that I'll be lulled into a aesthetic slumber and get lazy with my design, rehashing the same details over and over. I think I can avoid that, at least for now. The making was easy because, hell, I've done it all before. There are no new techniques here. I made the box quickly. I didn't have to figure anything out. I could just work. In fact, it took me longer to finish it (because of the paint). Thoughts of a random nature:

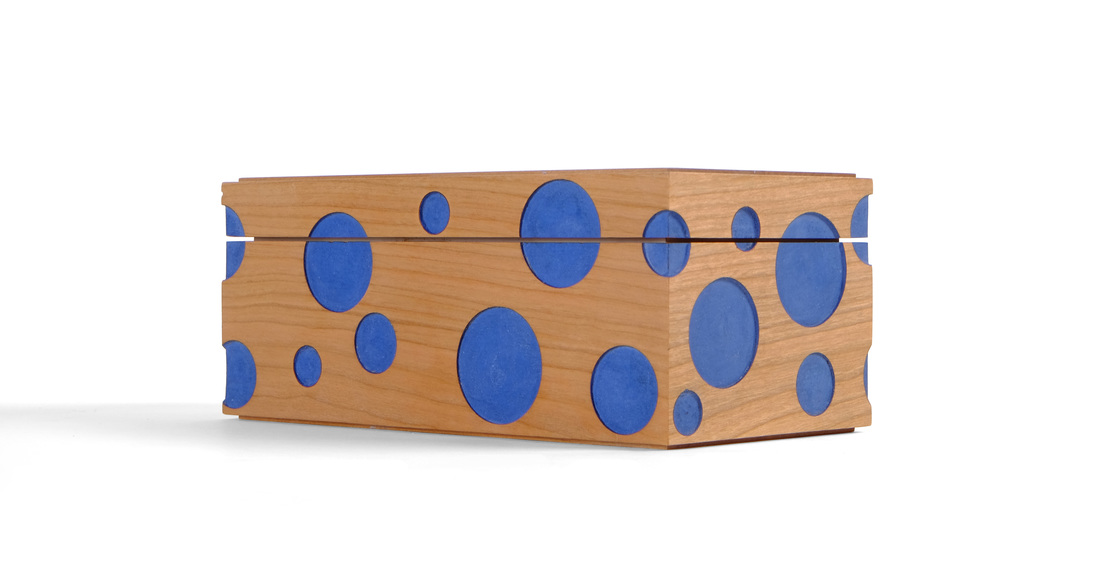

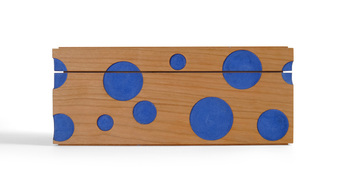

I was tempted to post nothing but photographs of this box. I think these photos say more than enough about the box, but I figure at least a few will want to know what the hell I was thinking when I designed it. So, I'll do some writing, too. This is one of the first boxes I thought of after deciding to attempt 52 boxes in 52 weeks. Honestly, I don't recall where the idea came from. I think something like it has been bouncing about my brain for several years. I do know that it was boxes like this one that inspired me to undertake the challenge. All of the boxes I've made so far have been nice, but some of them really didn't push me aesthetically. I fell back into my comfort zone. This box is definitely not one of those. What appeals to me about this box is how strong a graphical statement it makes. I love that the blue circles dominate the box. The riftsawn cherry I used for the sides is really just a background color. That's what I wanted. This box is about color and geometry. (But note how the cherry's grain rises and falls with the larger circles. This symmetry between the grain and pattern of the circles helps the grain disappear. Again, design is always in the details.) This also is why the top is made from some book matched and riftsawn cherry. Keep the grain quiet. Don't distract from the sides. I thought about adding a few circles to the top, but I'm glad I didn't. That would have been too much. This box took a long time to figure out and make because it is technically challenging. The blue circles you see are actually about 1/16 in. deep. At first, I was going to drill through a thin, shop sawn veneer, paint the underlying substrate and then glue the veneer to the substrate. I thought and thought about how to do that and still get a good four corner match. All the solutions I came up with were too fussy. I then moved to the idea of making a template and routing the circles into the sides. That's what I did, but I need to thank Mike Pekovich for helping me figure out exactly how to do it (Mike and I have some great mind melds every now and then when we bat ideas back and forth, developing them—sublating [google Hegel and aufheben] them, really—as we go. These always seem to benefit me. I doubt I've ever helped Mike. He's a technical genius.) After cutting the sides to length, I laid them out in order (front, side, back, side) between two fences and two stops at the ends. A long template fit over the top of the sides. I then routed the circles with my DeWalt 611 with the plunge base. I used a 1/2 in. diameter "dado clean out" bit from Whiteside. (It's the same bit I use with hinge mortise jigs.) This arrangement allowed me to wrap circles around the corners. I don't know if any of that makes sense, but I took some pictures and I'll post them to my Instagram account (kenney.matt). Here's another important part of the design that also involves technique. Some of the circles bridge the bottom and top. I cut the top free at the bandsaw and then sanded the top and bottom on a piece of sandpaper stuck to my tablesaw to get rid of the machine marks. The cutting and sanding removes material and part of the circles. If the top sat directly on the bottom, you'd see a disruption in the circles' circumference. To overcome this, I used the box liner to raise the top and create a gap equal to the material removed. (Remember when I did this with box 12? I was testing out the technique so that when I made this box, I'd have it figured out. I've been working on Box 30 for a long time.) I need to thank Mike for planting the seed for this in my mind. I come to him with crazy ideas and the beginnings of how to get it done and he helps me get to a solid technique for doing it. I don't know what else to say. The box is the same size as boxes 28 and 29. The top and bottom are glued into rabbets. They're plywood—painted on the inside face and covered with shopsawn veneer on the outside. The liner is cherry, too, but painted with light cream milk paint from Old Fashioned Milk Paint. The blue for the circles is my old friend, Federal Blue. Looks like random thoughts are back on the menu, boys!

|

AuthorI love furniture design, and smart techniques. This blog is about both. Archives

August 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed